Having followed a month of tempestuous headlines, editor Hamish Kilburn has come to the stark realisation that more education is needed in order to project equality in the global architecture and design arena…

I sat alone peering over London’s Leicester Square from a unique vantage point at a swanky rooftop bar. Glancing down, I was able to capture the colourful scene that was taking place below. Inspired, and feeling immensely proud, I began writing my latest Editor’s Letter, which gave a nod to diversity in design. It was Pride London 2019, and the square was packed – social distancing hadn’t yet been conceived – and I remember thinking how beautifully raw, eclectic and accepting the capital felt as the confetti cannons sounded while equality echoed from all surfaces.

Fast forward one year and here I am today, this time feeling somewhat melancholy while writing my monthly column for what feels like a parallel publication to one I was editing 12 months ago. I’m knocking on the doors, but hospitality is closed (for now) and no one appears to be home. ‘Covid-19’, a phrase we didn’t know existed in 2019, has infected my inbox, and every story in it. There’s hope, though. July 4 is re-opening day for many, but as I begin to feel optimistic (and I really am optimistic about hospitality post-pandemic), the next article I read in my morning catch-up of the headlines prevents me from showing any sign of euphoria.

A 46-year-old black male, named George Floyd, has died in the hands of two white policemen. It began with a report of a fake $20 (£16.20) bill, and ended with the death of Floyd after one of the policemen knelt on his neck, while blatantly ignoring the man’s pleas for help, for an agonising eight minutes and 46 seconds.

The footage of the incident spilled into the boundless realms of social media with the hashtag BlackLivesMatter. And like the virus itself that put a halt on our industry and forced us to adapt to meet new consumer demand, the protests for equality went global.

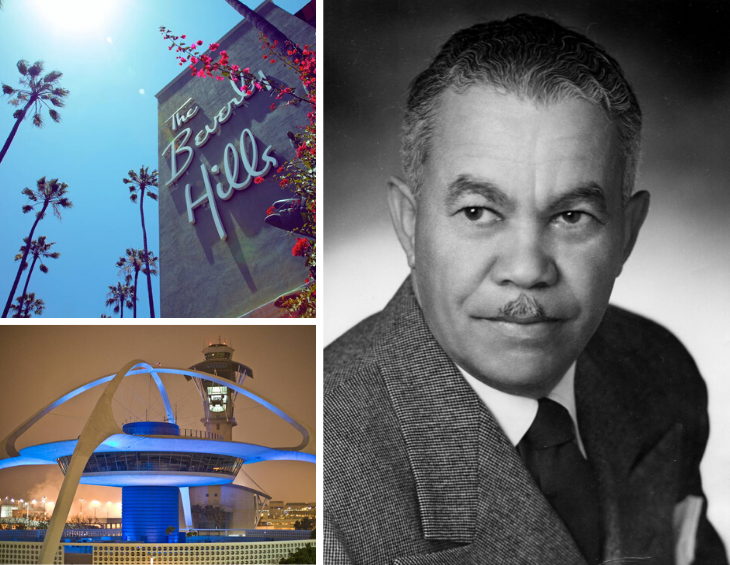

While on the one hand I felt concerned that social distancing and heart-felt protests are a fractious pairing, I also felt compelled to read and learn after seeing a friend’s status, which read: “I understand I will never understand. However, I stand.” It was at that point when I decided to delve into the history of our industry, and when I first read about John R. Williams and everything he was able to achieve while working in and for a society that today we would be ashamed of.

“He designed more than 2,000 homes (all of which differed in styles) and his clients included many celebrities, including Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz among others.”

Williams was an architectural pioneer who was largely responsible for Hollywood’s eclectic, colonial and California ranch-style architecture landscape. He designed more than 2,000 homes (all of which differed in styles). His clients included many celebrities, including Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz among others. In addition, the trailblazer designed other buildings, such as the Mutal Life Insurance Building and the LA County Courthouse. He also worked on the design of the iconic googie-styled Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, and in the 1940s, he was part of the team who redesigned of The Beverly Hills Hotel.

Having grown up as the only black child in his elementary school, Williams recognised that his clients of that era would feel uncomfortable sitting directly next to a black man, so he learned to draft and sketch upside down. And to avoid his clients having to shake his hand, he would often walk and talk with his hands either behind his back or in his pockets.

The real irony, in my opinion, was that so often Williams was not allowed to visit the public places he so painstakingly designed. Williams operated, where possible, under the radar in order to survive as a black architect in the western world.

“In 1957, he was the first Black architect elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).”

In his career that spanned five decades, according to the Paul R Williams Project, William’s not only imagined thousands of buildings, but he also served on a number of municipal, state and federal commissions. He was carefully active in political and social organisations, which earned the admiration and respect of his peers. Williams frequently donated his time and skills to projects he believed furthered the health and welfare of young people, African Americans in Southern California and the greater society. In 1957, he was the first black architect elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

Williams retired from practice in 1973 and died in 1980 at the age of 85.

In 2017, his name joined legends such as Sir Norman Foster, Frank Gehry and Renxo Piano. Williams was posthumously awarded AIA’s 2017 Gold Medal, which is the highest annual honour that recognises individuals whose work has had a lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture. In consequence to his many achievements, he is known today (and is documented in the history books) as Hollywood’s Architect.

Hotel Designs is not a political platform. It is, however, an educational podium where trending topics are discussed, debated and amplified. Racism and inequality in general is recurrently guised, and it is so rarely in plain sight. I hope that by looking back and identifying injustices, like how Williams felt forced to work under the radar (and arguably work harder than any other architect of his era), we can together ensure that history doesn’t repeat itself and instead celebrate and promote people for their talent and their talent alone, regardless of race, sexual orientation, disability and social standings.

I understand I will never understand. However, I stand.

Editor, Hotel Designs

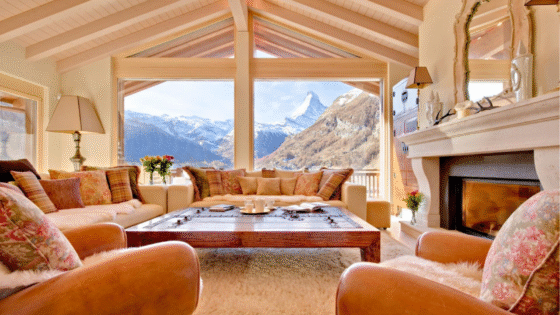

Main image credit: Dorchester Collection/AIA