Having spent more than 40 years exploring Africa as photographers and filmmakers, Dereck and Beverly Joubert, the founders of Great Plains, have new standards in sustainability, hospitality and humanity. Editor Hamish Kilburn catches up with the dynamic duo to understand authentic luxury hotel design through a wider lens, capturing a broader perspective when it comes to hospitality in the wild…

There is something about Africa – the woodlands, wetlands, and seemingly never-ending grasslands in-between – that gives life deeper meaning. I’ve noticed that the sun sets differently here, almost feeling like you’re closer to the sun than any other continent on earth is.

My experience in Africa is a millisecond, though, compared to the time that Dereck and Beverly Joubert have invested in order to learn about this great natural world. Having spent more than 40 years’ exploring these plains as filmmakers and photographers – the pair have produced more than 25 films for National Geographic – to call these two wildlife and conservation experts is an unruly understatement.

In 2006, to fund their wildlife conservation work, Beverly and Dereck channeled their wisdom and love of nature and started a new hospitality venture. Their inspirational journey – which went on to challenge the cookie-cutter approach in safari travel, architecture and design – began when they set up Great Plains, an authentic and iconic tourism conservation organisation.

Today, the brand shelters 16 safari properties, in Botswana, Kenya and Zimbabwe, each designed through the director’s lens to tell unique stories that enhance each camp’s very special sense of place and built to celebrate each destination’s individual character.

- Image caption: Filmmakers Dereck and Beverly Joubert, co-founders of Great Plains, design each camp themselves. | Image credit: Duba Plains, Great Plains

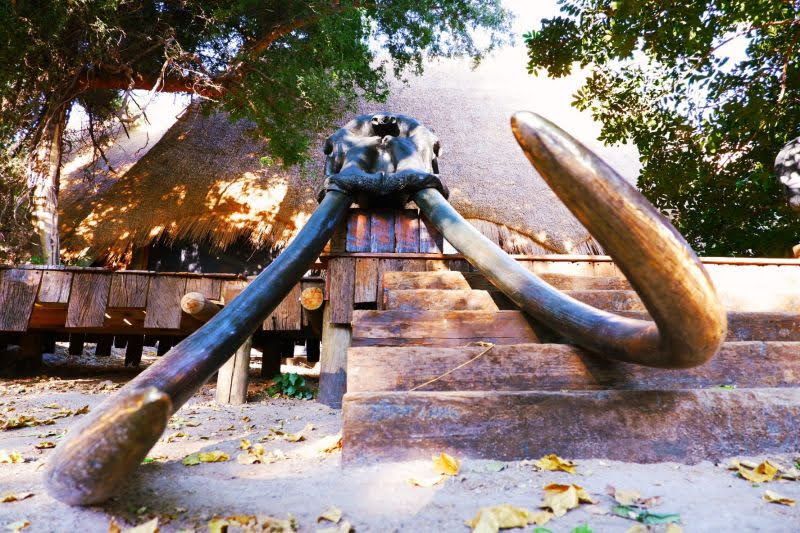

- Image caption: All 16 camps in Great Plain’s portfolio are sustainably designed to offer unique luxury perspectives on nature. | Image credit: Duba Plains, Great Plains

Despite being award-winning filmmakers, world-renowned hoteliers and selflessly good human beings through their ongoing charity work, there is not a shred of haughtiness about Beverly and Dereck, as I learn when I catch up with the husband-and-wife team to understand how they, through a purposeful and sustainable approach to luxury hospitality, are helping travellers to capture one-off experiences from a slightly different perspective.

Hamish Kilburn: What initially made you audition for the roles of ‘hotelier’?

Beverly Joubert: We’re explorers, conservationists and filmmakers. As we started the Big Cats Initiative at National Geographic, we soon realised that saving lions one at a time was futile and we needed to conserve large landscapes to save everything in them. To afford this, we decided on high-end tourism as opposed to philanthropy.

Dereck Joubert: To be honest hospitality runs deep in Africa; in our DNA where of course we were all born, so we were inspired by that spirit of coming home and being welcomed. As a result, as I design our camps, I do it with two ’stories’ in mind: the three act ‘ welcome home’ one and whatever story I want to tell through the design of that unique place.

Image caption: In 2006, to fund their wildlife conservation efforts, filmmakers Dereck and Beverly Joubert launched Great Plains.

HK: What amendments have you made to the existing script of safari in Africa?

DJ: Oh, I don’t think we have amended the African safari – it transcends us! It may have been about the physical journey (safari being quite simply a journey in Swahili) but if anything I hope we expand it to an inner journey as much as a physical one. Our version of safari is one where you can explore your roots, from millions of years ago, and interrogate your relationship with the other creatures here, our history with them, our very profound and interwoven dependancy. For example there was an ancient cat called Dinofelis that stalked the caves we sheltered in 3.5 million years ago, and possibly forced us out into the grasslands more where we discovered fire and bone marrow that gave us strength, intelligence and the ability to no longer fear large spotted cats. Today we seek out leopards to marvel at their beauty rather than shy away in fear, but we’ve walked this journey of the safari together.

BJ: What does the resonance of meditating at a waterhole with elephants nearby as they rumble do to you? How can we each for that creative energy that the early philosophers and poets sought out in the wilderness, uncluttered and pure. In the style of our camps, we try to add detail and story telling like this in design, in service and as an experience.

- Image caption: Set in one of the most pristine wilderness areas left on our planet, the Selinda Camp rests on the banks of the Selinda Spillway, as it enters the Linyanti River. | Image credit: Great Plains

- Image caption: The private 130 000-hectare Selinda Reserve boasts elephants by the thousands, regular sightings of the Selinda pack of African wild dogs as well as the famous Selinda Lion Pride. | Image credit: Great Plains

HK: What is the current narrative in Africa?

BJ: The Covid-19 death rates in the USA is at about 800 per million people. In Botswana it is 2 per million, so the safety and risk are worlds apart. The outdoor experiences reduce the risk dramatically, but no matter what the rates are, the closed borders have obviously collapsed tourism.

What is evident is that we’re in a cycle of demise that can cause spiralling circles of pandemics. As a result of our nefarious relationship with wild animals placed in captivity in cages in wet markets (in this case), we have sparked an economic crisis, global shutdowns that will lead to a recession, closed borders, and tourism, that communities rely so heavily on in Africa and other places.

DJ: The loss of income has led to many turning to nature to feed themselves at a time when game wardens and anti poaching patrols have been cut back. This perfect storm has led to a second pandemic of destruction of wildlife and a renewed trade in illegal wildlife and bush meat, that find their ways into the wet markets again. So we are seeing a second and third wave of new unexpected viral pandemics as a result. We have to shut down wet markets and the trade in wildlife. We have to review and renew the ways we engage with all animals . We started Project Ranger to support rangers who have been furloughed and keep wildlife areas intact and protected. We have to ensure that there is actually something for travellers to want to seek out when this is all over.

HK: What makes your cast of 660 employees special and unique?

BJ: It is an ensemble cast isn’t it?! I think that the way we work at Great Plains is as a small family business, with a family of employees who do more than just show up. Hospitality in general requires skills that are more involved than that any way – much close to the work as performers – each day to smile and engage in a pleasant way no matter what is going on in your life. I recognise that, so we are sensitised to this and have a policy of support. If a guide is having a bad day, another is primed to reach out and ask him or her what is going on and to step in. Managers do the same to their staff and actually this starts at the top and someone who just joined our EXCO meetings pointed out that I start each session asking each Managing Director what we can do as a whole group to help each week. I know the names of all our staff and most of their families and I don’t want to grow it beyond that point where it becomes impersonal and corporate.

HK: Can you talk us through the filmmaker process of storyboarding each scene/camp?

DJ: Each hotel or in our case, camp, is a story. I start with an overall direction and message. In the Selinda camp, for example, I wanted us to re-evaluate our relationship with elephants. The camp is in the heart of the highest density of elephants in the world, but in the past, early explorers like Livingstone and Selous travelled through these areas with guns and a desire for ivory. Selinda was a hunting concession for decades and when we took it over we stopped all killing.

Our relationship with elephants is symbolic of our loss of harmony, so therefore harmony was the solution to ’the question’ the area and the elephants themselves impose on us.

Now I obviously didn’t want to simply populate the décor with elephant images – that would be too easy and cheap. Instead, I designed and cast two life-sized bronze skulls of elephants including bronze tusks but in the forehead of one I had the words “homo nosce the Ipsum” cut in, and in the other “homo nosce pe Ipsum”, which is Latin for “man know thyself” and “man forgive thyself”. The sculptures are placed on either side of the main entrance with the intention to stimulate a real conversation that starts with us understand who we are and what we have done over the centuries to their peaceful animals, but then to forgive ourselves (and our ancestors) for who we are.

But that is just the first act, and I wanted to design this with a longer and deeper path towards harmony which in Eastern teachings leans towards the laying out of five fundamental elements the first being the metal skulls, but then you enter a chamber with blue touch of furniture, to represent water and often our guests arrive by boat so I imagined them dragging that element with them, like a smoke trail from the river. Next, you enter for a welcome tea; an open space with a flowing white silk roof to represent air. Beyond that you pass through an open dining area with brown tables, where we serve fresh largely plant based food from the earth, and then to the fire and off to the third act and your resting place, in your room, presumable in perfect harmony and balance.

- Image caption: Each camp is designed individually. The Selinda Camp, for example, has been designed to celebrate elephants. | Image credit: Great Plains

- Image caption: Dereck and Beverly Joubert designed and cast two life-sized bronze skulls of elephants including bronze tusks for the Selinda Camp. | Image credit: Great Plains

Only once we understand who we are, and forgive ourselves will we be able to cross a threshold, as one does in this camp, into a new unburdened relationship with both ourselves and elephants, like stepping through a vortex.

It’s not just a story though, I believe that most people arrive and feel that tranquility and settle because of the balance we have created, and so many arriving guest actually sign deeply as they enter this story, this camp. If I can I will briefly describe Mara Plains, that I felt should be an architectural and physical meeting place, also in harmony between three often opposing cultures: The Maasai, the Swahili, the colonials.

But as explorers for National Geographic, we wanted to be the glue as one is behind the lens. So I oriented the camp based on a single and lone tree five km away, drew a line through the camp, and angled it all around this tree. Then I drew a Fibonacci proportion in the ground and had the tent makers make the main tent exactly to those proportions, representing the ideal gold rectangle one uses in a 35 mm picture frame.

Inside the camp, we imported 75-100 year old railway sleepers as recycled wood (teak) and brass from the original Blue Train 120 years ago. Reds from the Maasai culture represent this very visual association and it didn’t have be head handed because we are in Maasai world so it is everywhere anyway, but the coastal Swahili culture has in influence here so the large Swahili doors behind the showers are a not to them, associated with the sea and water. Each tent fits the Fibonacci proportions creating a film set styled ration that takes you back to the romance of the 1920’s adventures but hopefully without the embedded racism and in appropriate colonialism of that time.

“I added my own collection of campaign furniture as templates and samples for cabinet makes to replicate, which happened at the time of the Indonesian Tsunami where thousands of artisans were left without work.” – Beverly Joubert, co-founder, Great Plains.

HK: How and where do you source your props/artefacts?

BJ: In some cases, we design and make them ourselves, like in Zarafa, in Botswana, which is based on the story of the first giraffe to be seen by westerners as it went on a journey to Paris as a gift to KingCharles X.

- Image caption: Dereck and Beverly source art and artefacts in a meaningful way. | Image credit: Great Plains

- Image caption: Dereck and Beverly take deep pride in how each camp is sensitively designed. Image credit: Great Plains

Here, I added my own collection of campaign furniture as templates and samples for cabinet makes to replicate, which happened at the time of the Indonesian tsunami where thousands of artisans were left without work, and where tons of mahogany used for houses were smashed down from house scale to ideal furniture scale. So we used the reclaimed mahogany and hired the artisans to make this campaign furniture that is now unique to Zarafa camp. In other cases we just come across something in a market or antique store that we love and can’t live without, so we don’t!

HK: How has your approach on sustainability helped the local community?

BJ: Well, we have delivered something like 6,000 solar lanterns to families that have perviously been off grind, and an amazing addition to that was that the principal of the local school wrote to thank us because school grades were going up because kids could do their homework after dark. I don’t think the kids liked having do that but… We send nine ladies with very little education from Botswana to India to learn solar circuit board manufacturing technology for six months and to return and develop local businesses from this. We’ve planted more than 5,000 trees and started tree growing initiatives. We have a Great Plains Academy to teach people about hospitality and who to bridge the gap from high school to university.

HK: It’s clear that, as wildlife filmmakers, you allow nature to call the shots – can you explain more about how guests can give back to nature during their stay?

DJ: To nature, our guests and followers get involved in help fund a rhino calf by naming stand securing its protection on the wild, or supporting Project Ranger to keep front line conservationists at work to avoid this second pandemic. We have a need for $20 donations towards solar lanterns for kids learning at night, as well as $45,000 to move a rhino and indeed, we need an army of ambassadors who don’t donate but lobby against the extraction of wildlife (via hunting or poaching and trade) with their local representative. Everyone can do something.

HK: What major lesson has this journey in hospitality taught you so far?

BJ: We can all learn from hospitality because it is all about kindness and care; paying attention to details and I find myself taking a lot more care just to find out how someone (even in my team) is doing, randomly, as if I am hosting the world.

HK: 2016 was a pivotal year for you both. Beverly you survived a fatel injury after being attacked by a buffalo while filming your latest materpiece. Dereck, did that event and your recovery change your relationship with nature?

DJ: You know the buffalo attack didn’t really change that relationship, as much as it changed our relationship with ourselves, in that I promised myself not to waste another moment, day or month not totally enjoying my life with Beverly (if I got her back, which I did four times).

HK: Has designing hotels changed your perception at all as wildlife filmmakers?

BJ: Interesting, probably in that it has made me (both of us, I think) understand story telling more, because if you base the entire design of a hotel on a story, as I do, and that is going to be its story for decades it had better be well researched and thought out. So our films have probably evolved into more layered and in depth stories and while I had not connected the two careers in many way, I can see yah prior to this, where I am designing spaces based on a deep philosophy like our relationship with elephants, or intersecting cultures there is more depth to our films.

“I think that all journeys are stories and we are all the heroes of our scripts.” – Dereck Joubert, co-founder, Great Plains.

DJ: A good example is the Okavango film/s where the story is about a river from end to end. But that wasn’t enough, so I re-read Dante’s Divine Comedy partly while Beverly was in hospital recovering from the buffalo attack. And in it, I found two parallels, one of our or my journey and Dante’s as he wove his way from purgatory to parade to find and be reconnected with his love (as I did, over nine months as Beverly slowly came back to life.) Regarding the journey of the river, I flipped the story in the theatrical release to start also in Purgatory (in the desert) and wind our story back to Paradise at the source. Those are the kinds of stories one tells around a campfire about the design of a hotel or camp, not always in a natural history documentary for National Geographic!

I think that all journeys are stories and we are all the heroes of our scripts, (why write yourself in as the bad guy) and we are the storytelling ape. But to us, as much as we love lions and elephants, there are opportunities as films to tell parables that hold up the mirror to our lives, so we can advance in our relationships, and in our new and renewed contract with nature.

HK: In a sentence, can you explain the synopsis’ of your next masterpieces/camp openings?

BJ: As I walked the banks of the Zambezi River, under spreading pod mahogany trees, I saw a movement in the shade; a herd of elephants ambling towards me chasing their thirst, right passed me and out onto the plains, sliding into the water, leaving me with the name for the new camp on this exact site; Tembo Plains: (elephant in Shona.)

Main image credit: Great Plains