Throughout October we are, for the second time this year, putting the spotlight on lighting. To kickstart this series, we reach out to Gary Thornton, senior project designer at neolight global, to understand lighting design from the inside.

The profession of architectural lighting design is a relatively young industry, even though the practise of what we do in determining where there is light and where there isn’t has been around for centuries.

Of course back then this was simply people deciding where to put candles or, as far back as the 9th century, where to locate oil lamps. But architectural lighting design as a more formal profession really only goes back to around the 1950s with the likes of Richard Kelly pioneering the practice, followed by people like Derek Phillips and Jonathan Speirs.

So what is lighting design and what is it that lighting designers actually do? I’ve lost count of the times I’ve tried to explain this to my friends who think we “choose where to put light bulbs”!

It can be easily forgiven that it is not a widely known profession. There is no formal educational pathway and many people stumble into the profession from a semi-related field of design and find themselves “doing lighting design” before they even realise what it is (myself included!).

As an example, our office comprises lighting designers with backgrounds in product design, interior design, electrical engineering, film and television, photography, sculpture and architecture. There are indeed well-established Masters degrees, or undergraduate courses in Theatrical Lighting Design, but this is not the case for Architectural Lighting Design. Something that has been brought up again recently in our industry.

Lighting

Lighting concerns itself with how people perceive their environment, yet because light is intangible it has an intrinsic, and often underestimated, role in all aspects of visual design.

Working in a medium which remains invisible until it strikes a physical surface means that we lighting designers must be as concerned with the nature of the surface and the biology behind the human eye as with the light which strikes it.

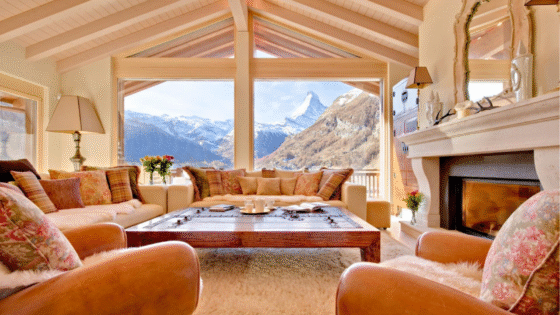

Ambient illumination, direct light, reflected light, the use of colour, areas of relative darkness and contrast all contribute to how a space looks and how it feels, resulting in designs made up of layers of light. The better lighting schemes consider what should be left unlit as much as what should be lit, so maybe we are just as much “darkness designers” as we are lighting designers.

Because of the immateriality, great lighting is rarely lauded. If you walk through a space and it looks and feels great then chances are it is because of the lighting. Not to take away from the interior designer, architect, or landscape designer that has typically designed more of the physical environment, but certainly in how the colours appear, how the material textures catch your eye, whatever the mood it prompts or the visual aesthetic it provides, it is because of the lighting.

Poor lighting on the other hand gets no end of complaints. Lighting that is overly bright or dark, too much glare, or feels cold and uninviting can make spaces feel uncomfortable so people don’t want to visit and spend time there. Even the best interior design schemes can be marred by bad lighting, and at the extreme bad lighting can even be bad for your health depending on the time of day or the tasks required of the people using it.

- Image credit: neolight

- Image credit: neolight

Lighting for hospitality

At the core of neolight’s work is the hospitality sector, and one of my favourite spaces to illuminate is the All Day Dining restaurant within a hotel. This is largely because it’s such a transformative space and great way to demonstrate the power of lighting. An All Day Dining restaurant needs to be able to provide a bright and fresh environment for breakfast, right through to the warmth and relaxing ambience of an evening meal.

When you get this right, the space will look and feel like a different restaurant to the guests from morning to night.

Lighting experiences

Architectural lighting design really started an accelerated upward curve with the mainstream adoption of LED. Since then light sources have been getting smaller and more efficient, and the fixtures themselves are increasingly packed full of technology.

Alongside this evolution of lighting technology has been an evolving expectation of the role of the lighting designer. No longer are we providing simple scene-setting schemes with smooth dimming to meet the client expectations, now clients are looking for more engaging and dynamic schemes concealed within the fabric of the building, with light that entrains and supports your circadian rhythm, they want an experience.

Yes the experience is framed by the architecture, or informed by the interior design, or the service that you receive, but transcending across all of those to make it a good experience is good lighting design.

Lighting design = experience design. And if that helps become popular on social media, then all the better.

To this end we are not just designers anymore. We have to be artists and scientists, knowledgeable in Bluetooth and LiFi, experts in daylight and green building codes, understanding biology of the human eye, of the physics of light, and all manner of material properties.

And this is all before we even mention the Internet of Things, where we are suddenly being asked about the limitations of LoRaWAN as a protocol to control light fixtures with.

Lighting is digital

There is an underlying expectation to all of this that we are digitally savvy. Lots of industries are going through change and digitisation, but lighting is changing right up there with them. In order to keep meeting the expectations of a modern day lighting design, we have to be able to understand and design with all these evolving elements.

One particular attribute that I’ve taken on is learning to code due to the increasing overlap with disciplines that do require this, and at the very least we need to be able to coordinate with them. For example, this is a prototype app written in Python that communicates with light fixtures in a hotel room to automatically adjust the colour temperature and brightness based on personal circumstances, such as jet lag.

Internet of Things

We have gone through the exponential growth of LED and now we have even further miniaturisation of technology so there is virtually nowhere that LEDs cannot be integrated, and conversely almost anything, like a sensor or a camera, that can’t be put back into light sources.

Lighting is a prime choice for the IoT to piggy back onto as it has an already existing ubiquitous infrastructure of power and data. This means that light fixtures can be used for monitoring space occupancy, improving shopping experiences, reporting crimes, and more.

But in order to be able to implement this we have to understand it, and that means lighting designers becoming experts in something else that isn’t traditionally “lighting”. It’s becoming experts in data, cloud servers, and Bluetooth meshes as part of the whole IoT network.

And this isn’t a trend that’s going away. At a macro level Smart Cities are well underway around the world (we are working on a Smarty City strategy for a brand new city in KSA at the moment), and on a micro level it’s using your voice to control the lighting in your own home. Lighting is a key part of the future of connected services.

Covid-19 will undoubtedly accelerate the demand for contact-free environments. Why carry a physical ID or ticket and have to touch door handles, when AI could verify you and open the door automatically? Why touch any number of surfaces and interfaces to check-in to a hotel, when facial recognition could automate this as you walk through the lobby and give you a “key” on your mobile phone?

In assessing these expected trends we see that lighting is well placed to provide this as part of the IoT. Retrofitting sensor-embedded light fixtures becomes much easier than ripping out ceilings, pulling cables, and installing new networks.

As part of this learning curve affecting lighting, designers are no longer just visiting project sites, but also visiting data centres that test these sensor embedded light fixtures and the data points that they capture to understand it first hand in order to be able to implement it as part of a lighting scheme.

Misunderstandings

As lighting becomes more understood it’s great to now be reading comments like this, highlighting the importance of lighting to a space.

But for every moment of understanding, we still work with wider design teams who still misunderstand what we do. Consultants that have heard of ZigBee or BLE, and so that’s how they want their lighting controlled – when in reality all they really need is a simple control plate.

Part of our role is taking a step back from the technology and really understanding the project needs. We won’t use technology for the sake of it, especially if it’s not needed and likely to end up not being used. How often have you struggled with a fancy lighting control system in a hotel guestroom when a simple rotary dimmer switch would have been just perfect?

As lighting design finds its way into mainstream vocabulary, more buzzwords like “human centric lighting” have come to the fore, which is another misconception to overcome.

Human centric design is human focussed design. At the heart of this notion is what we have been doing for many years now. Designing for humans. Lighting for humans. Lighting for, and with, people at the centre.

The future

Who knows what the limits are to where lighting will reach – even a few years ago we were barely imagining what we have today of subscription models offering Lighting as a Service, secure wireless data through light in LiFi, and even highly secretive LED spectrum recipes used in horticulture to maximise crop yield!

Of what I have no doubt is that as lighting design continues to advance and evolve, so will the humble lighting designer along with it.

Main image credit: neolight