#8 Defining luxury – how wellness spaces are evolving

https://hoteldesigns.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Hansgrohe-report-560x315-1.jpg 560 315 Hamish Kilburn Hamish Kilburn https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/81d2884aeeac3c45e38c47cacc508c2178bab773320ff2d6a83bdcc803d93aec?s=96&d=mm&r=gThe latest Hotel Designs LAB report has been born following the slow yet steady evolution of what consumers understand luxury to mean to them. In an 18-page report, Hotel Designs, Arigami and a team of contributors explores the new pillars that are helping designers redefine their approach to water-related spaces.

Meet the contributors:

- Steffen Erath, Head of Sustainability & Innovation, Hansgrohe Group

- Anke Sohn, Head of Global Marketing, AXOR

- Hamish Kilburn, Editor, Hotel Designs

- Benjamin Holzer, Head of Product Management, AXOR

- Phillipe Starck, Founder, STARCK

- Ari Peralta, Founder and CEO, Arigami

Designing in tune with nature will be the new maker of how we view luxury in our eco-friendly and health-conscious society. To do this, it is important for designers to understand the environmental image of each design choice and how it sits within a circular economy.

- Image credit: Hansgrohe

- Image credit: Hansgrohe

The new pillars around luxury, identified in the report, are:

- Simplicity

- Transparency

- Materiality

- Longevity

In addition to understanding the science, the paper also explored the Hansgrohe Group EcoSmart Technology as an example of a forward-thinking tech-savvy product, which consumes up to 60 per cent less water, that is meeting consumer’s demands for luxury, wellness and sustainability in 2022.

The report concludes with the idea that sustainability is just as important in the bathroom as in any other space in the hotel, suggesting that designers, architects and hotel experts should consider making meaningful changes with the whole property in mind.

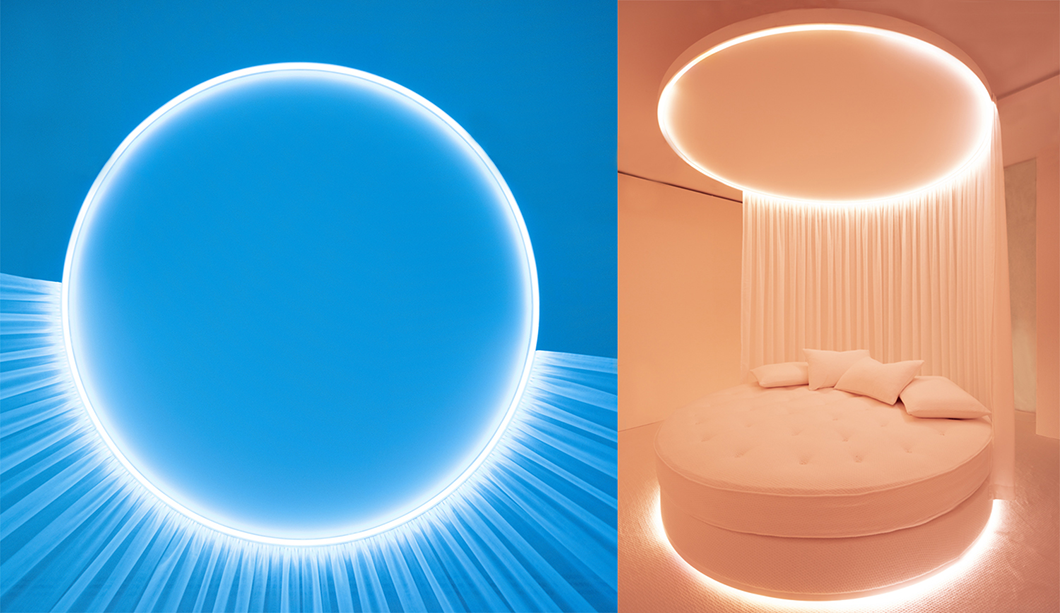

Main image credit: The Hansgrohe Group. AXOR conscious shower designed by Philippe Starck