For the final installation of Hotel Designs‘ three-part International Women’s Day series, Meghan Taylor is looking at how 20th-century women shaped today’s design world…

Throughout history, female designers and artists have not only challenged conventions but fundamentally reshaped the way we think about design and the spaces we inhabit. By pushing against gendered expectations in art, architecture, and interiors, they redefined creative expression and built a foundation for future generations.

Here, I’m exploring how key 20th-century women in design – through radical installations, furniture innovations, and surrealist visions – exposed biases in domestic spaces and transformed the built environment. Their work was not just about rebellion; it was about constructing new possibilities. They didn’t just participate in design – they redesigned the future.

Womanhouse: redefining domestic interiors

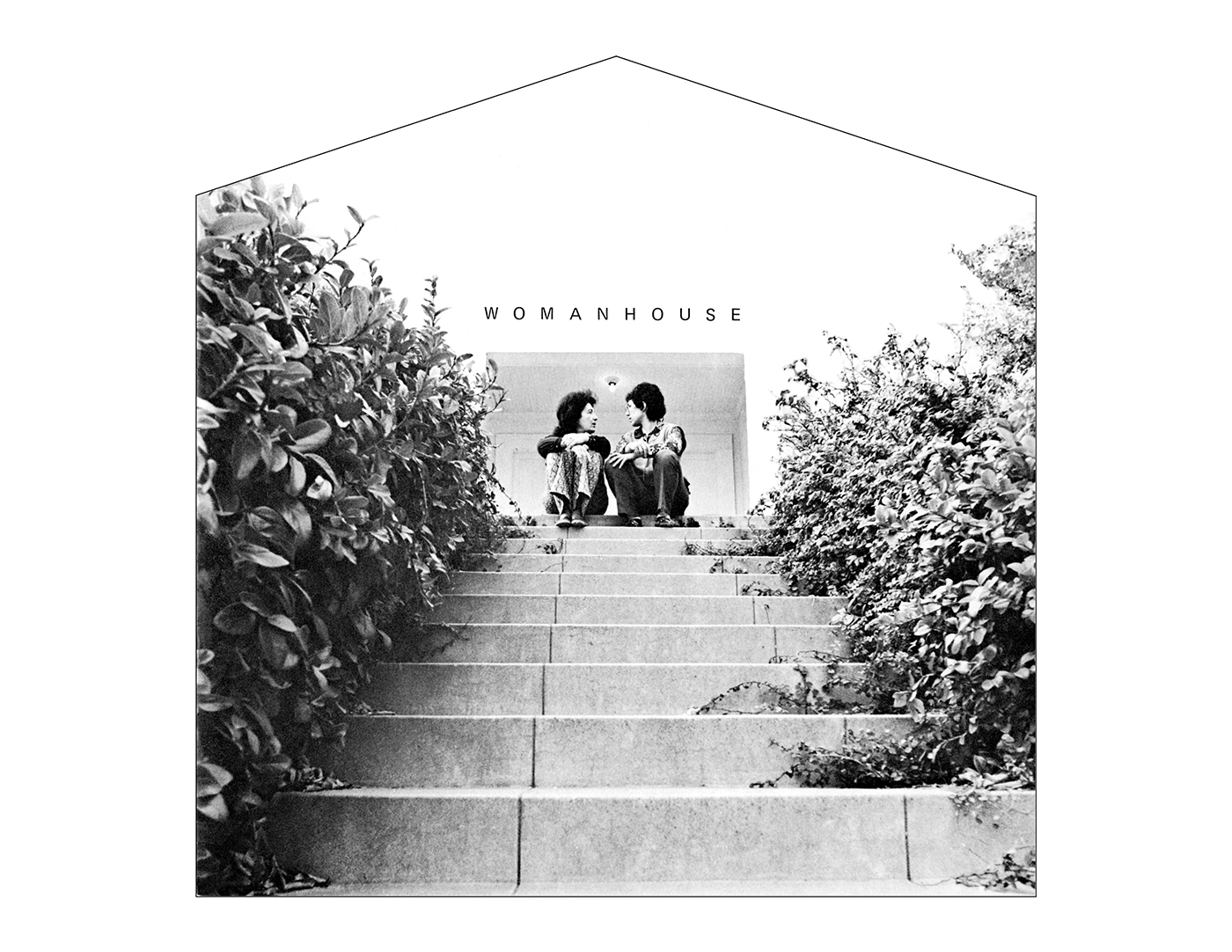

Womanhouse catalogue cover featuring Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, 1972 | Image credit: Though the Flower Archives housed at Penn State University Archives

With the full WOW!house 2025 designer lineup and room concepts revealed this week, I was reminded of Womanhouse – a ground-breaking 1972 Californian art installation that challenged traditional ideas of domesticity and gendered space.

Organised by artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, but inclusive of more than 20 female artists, Womanhouse was more than an art exhibition; it was a radical act of reclamation which took over an abandoned 17-room Victorian house in Hollywood, transforming it into an immersive critique of domestic femininity.

Before any art could be created, the women also undertook the physical labour of renovation, learning the skills and using power tools to clean, paint and rebuild the space – installing new windows and electrics too.

-

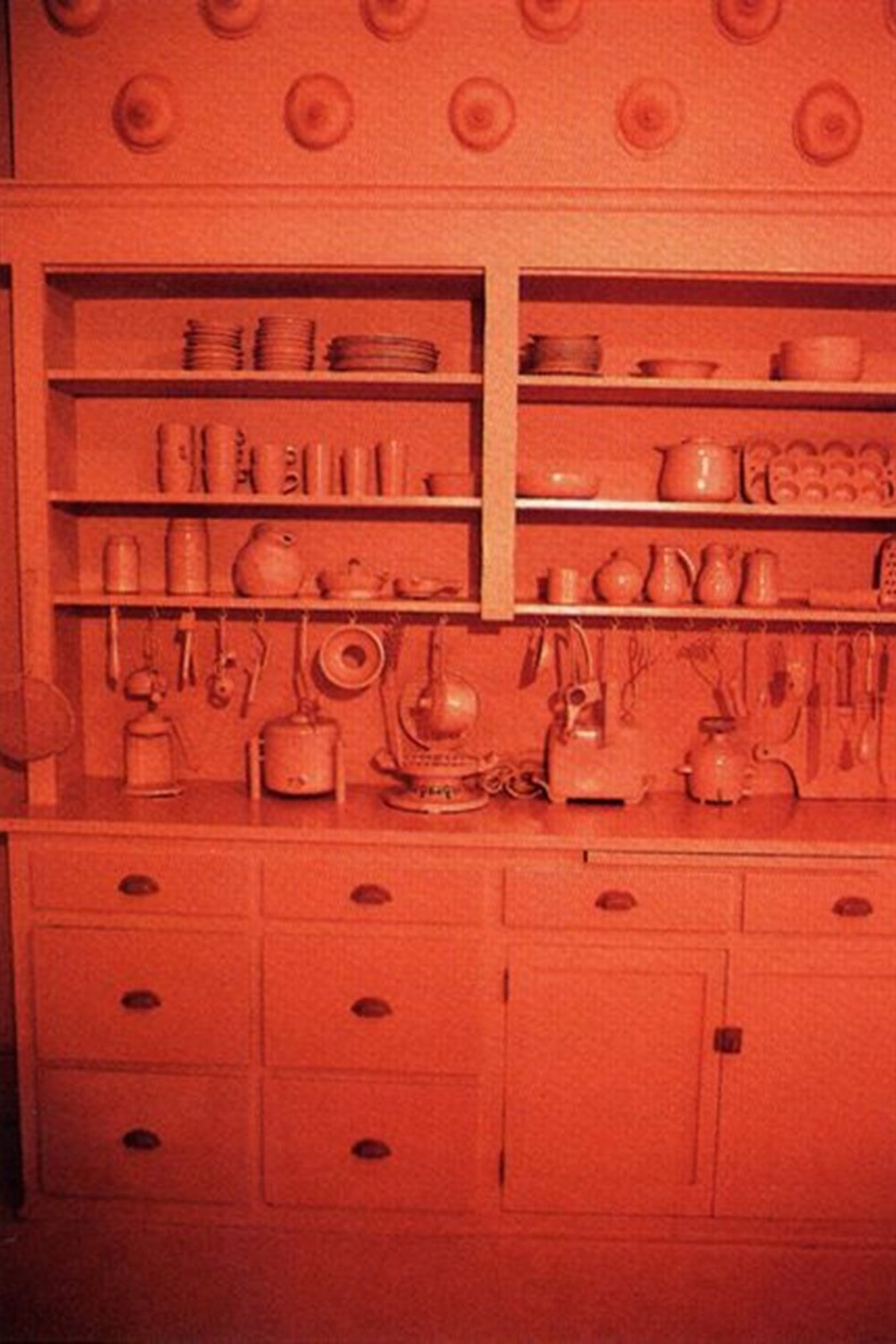

- Nurturant Kitchen, 1972 | Image credit: Miriam Schapiro Archives on Women Artists, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries

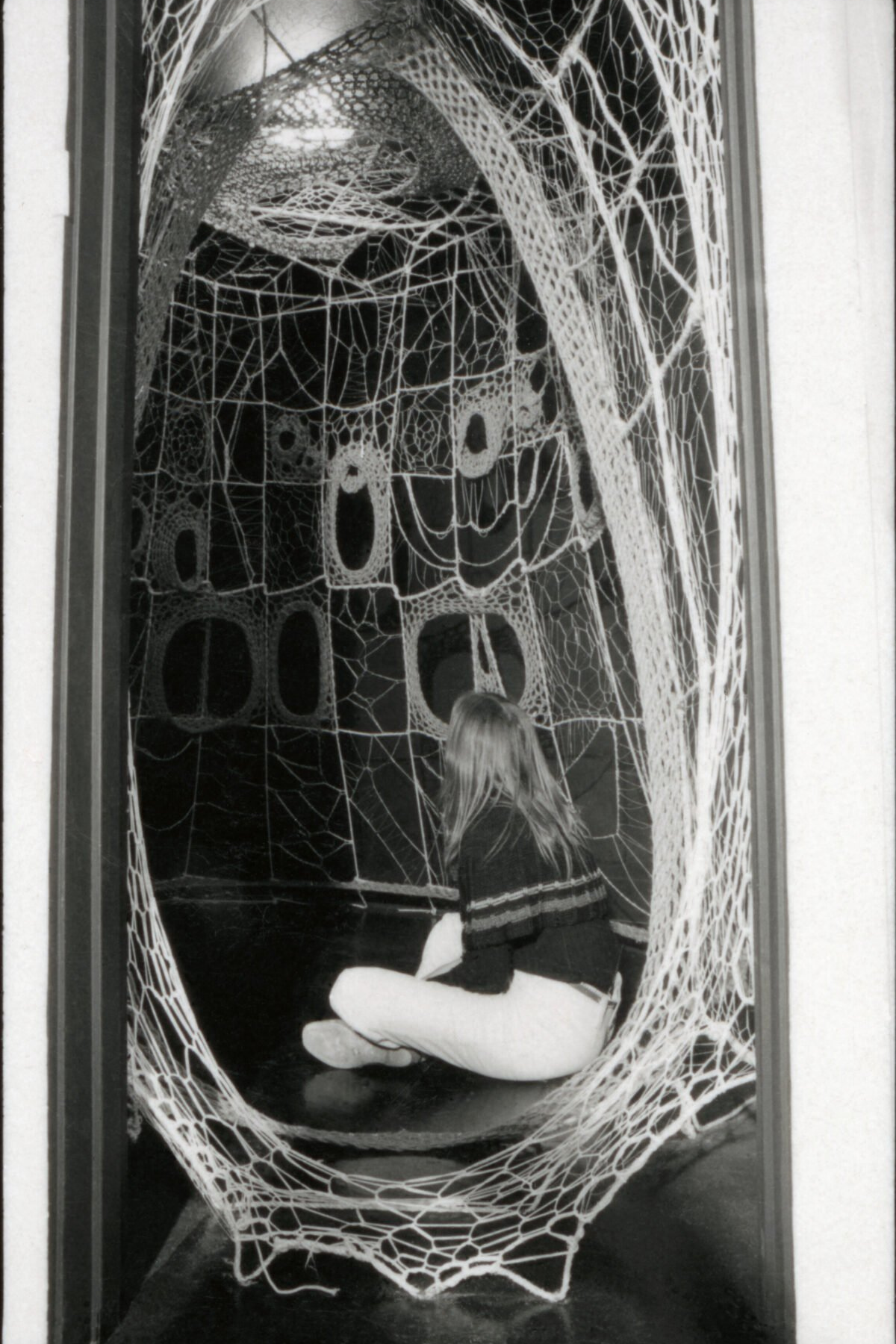

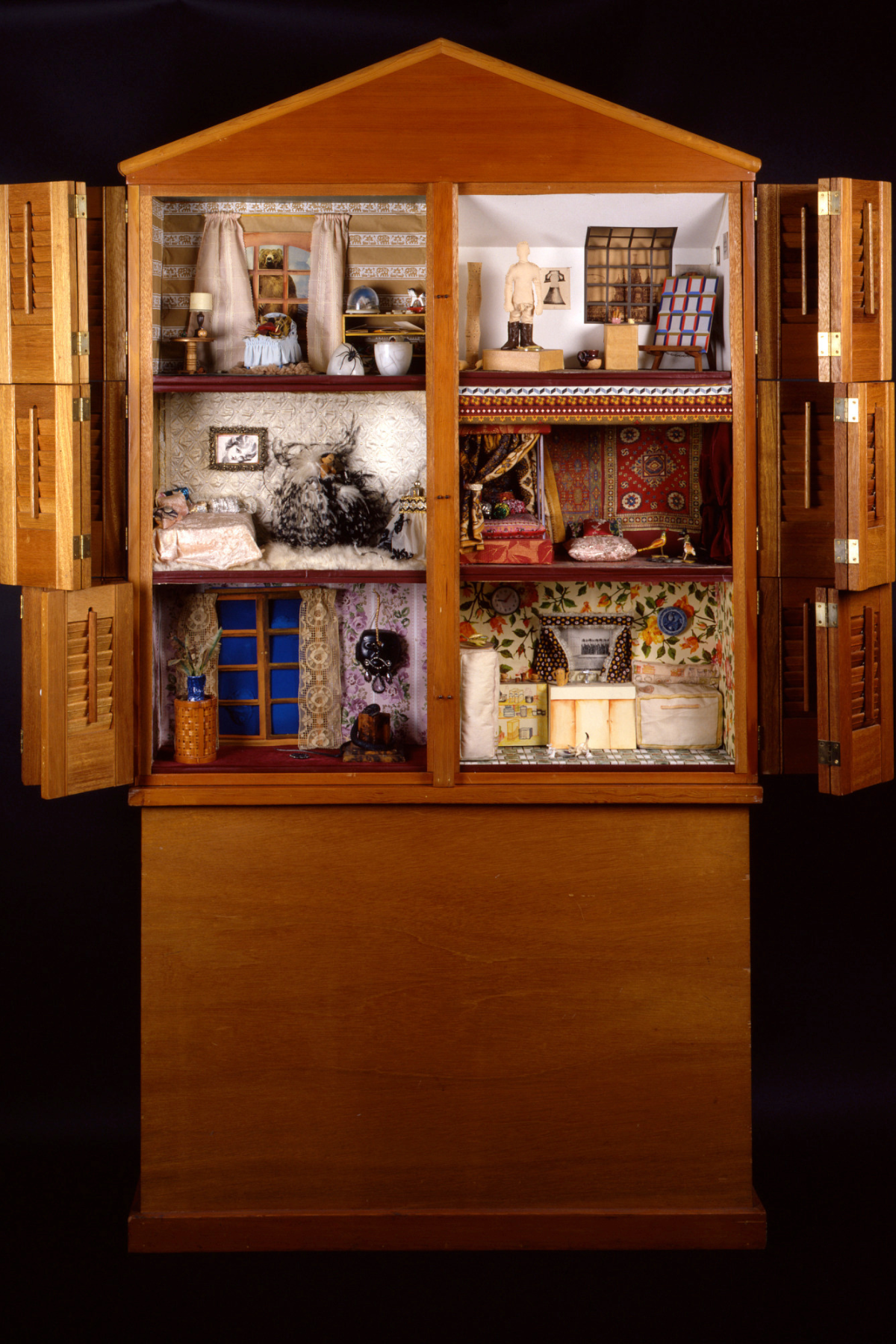

Each exhibition room became a conceptual statement, exposing the limitations of traditional roles. The Nurturant Kitchen turned the kitchen into an assembly line, stripping it of its warmth to highlight its dehumanising effects. Faith Wilding’s Crocheted Environment transformed delicate textile work into an enveloping, womb-like structure, reclaiming femininity as a force of power and protection rather than submission. The Dollhouse juxtaposed the supposed safety of home with the hidden terrors lurking within its walls.

By dismantling the idea of domestic space as passive and feminine, Womanhouse didn’t just critique the present – it envisioned a new relationship between women and the built environment. Its impact continues to resonate in contemporary architecture and interior design, where gendered assumptions about space are still being challenged.

Nanna Ditzel: reshaping modern furniture

Nanna (right) and Jørgen Ditzel | Image credit: Nanna Ditzel Design

A pioneering Danish designer, Nanna Ditzel refused to conform to the rigid, masculine-coded minimalism of mid-century modernism. Instead, she brought movement, colour, and organic forms into furniture design, paving the way for a more expressive and inclusive future.

Born in 1923 in Copenhagen, Nanna studied at the Danish School of Arts and Crafts before launching a studio with her husband, Jørgen. Her work blurred the boundaries between form and function, proving that furniture could be both practical and emotionally engaging. The 1959 Hanging Egg Chair, a now-iconic design, defied the static nature of traditional seating, offering a suspended cocoon of comfort and freedom.

Two of my favourite designs, the Butterfly Chair and Sea Shell, embody Nanna’s signature approach – organic shapes, bold colours, and playful curves that directly opposed the stark, neutral minimalism of the time.

Unlike many of her male contemporaries, she embraced fluidity and softness, recognising that modern design could be dynamic rather than rigid.

As her career evolved, so did her vision. Later designs, such as the Bench for Two, encouraged community and interaction rather than isolation, reflecting her belief in design as a social force.

Her legacy is evident in today’s continued love for Scandinavian design and in the work of female designers like Patricia Urquiola, who similarly reject traditional constraints in favour of innovation and inclusivity.

Leonora Carrington: repainting the female future

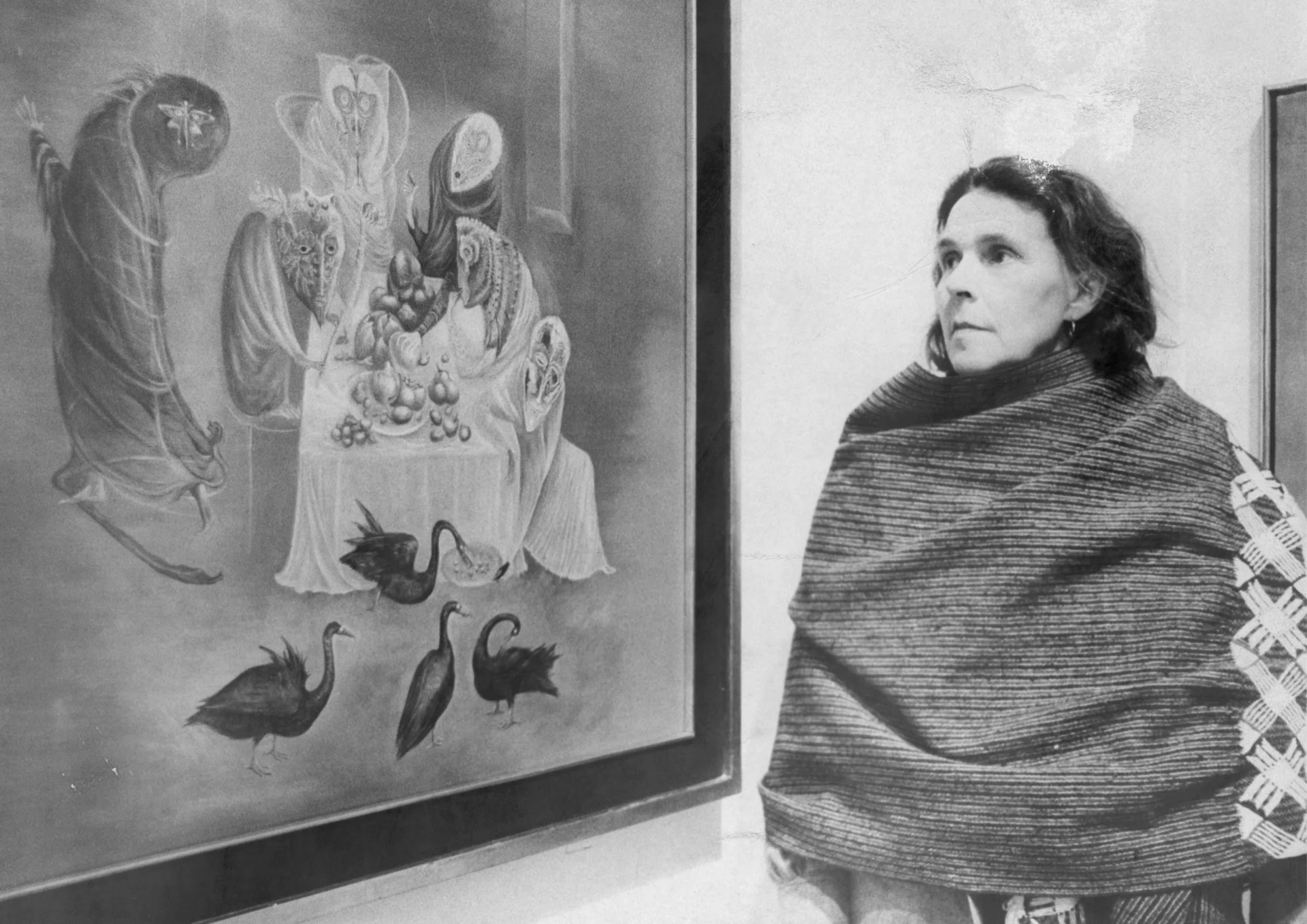

Leonora Carrington with Lepidotera | Image credit: Jerry Engel / New York Post Archives

Trawling through an abridged history of Surrealism, while writing my undergrad dissertation, it was clear that male voices had dictated much of the movement’s earliest discourse. Then I discovered Leonora Carrington. A naturalised Mexican but Lancashire-born artist, writer and designer, with a love for horses, mythology, Lewis Carroll, and the absurd, she didn’t just catch my attention – my eyes nearly popped out my head! Her work was unapologetically feminist, using myth, fantasy, and the surreal to challenge patriarchal norms.

In Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) (1937), Leonora subverted the traditional male gaze by staring directly at the viewer, claiming her own agency. Later, in her 1974 novel The Hearing Trumpet (a must read), she used satire and surrealism to dismantle stereotypes of aging and womanhood – proving that feminism in design wasn’t just about youth and beauty, but about autonomy at every stage of life.

Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) | Image credit: 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Leonora’s influence extended beyond the canvas. In Mexico, she collaborated with indigenous artisans, integrating Surrealist motifs into textiles – a craft often dismissed as ‘women’s work’. By elevating these forms to high art, she challenged the hierarchy that separated fine art from craft, paving the way for contemporary textile artists and designers.

Even in death, Leonora continues to break records. In May 2024, her painting Les Distractions de Dagobert sold for £22.5 million at Sotheby’s, making her the highest-selling British-born female artist at auction.

These women didn’t just challenge norms; they built new foundations. Womanhouse dismantled the gendered assumptions of domestic space, Nanna Ditzel reshaped modern furniture to embrace movement and emotion, and Leonora Carrington infused surrealism with feminist defiance. Their work continues to shape contemporary design, proving that the future isn’t just something we inherit – it’s something we design.

Main image: Leonora Carrington’s And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur | Image credit: Museum of Modern Art, London