Editor Hamish Kilburn was given exclusive access inside the archive of Sanderson Design Group to flick through centuries worth of design under one roof and, ultimately, understand the context of the group’s latest collections…

Hidden from view on the outskirts of London, is where Sanderson Design Group (SDG) perhaps unexpectedly shelters its most previous and valuable hidden treasures, 230 miles away from where the fabrics are printed in Lancaster. Along with the group’s latest collections, it is where the Sanderson Design Group’s archives is being perfectly preserved.

Protecting this library is Dr Catherine Sidwell, Senor Archivist at Sanderson Design Group, who means it when she says that photography is strictly prohibited. Sidwell, a design historian who, prior to joining SDG, worked at the V&A museum as a curator and managed exhibitions at the Powerhouse in Sydney. Sidwell kindly explained the value of the group’s archive as we rummaged through hundreds of years’ worth of design trends – time really did stand still as we carefully pieced together how today’s design team at SDG – who crucially work in the same building – use these historical treasures to confidentially produce tomorrow’s collections.

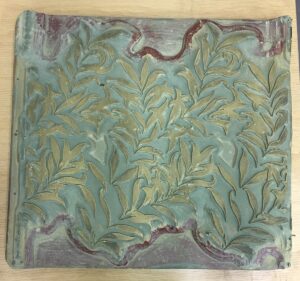

Image credit: Morris & Co

With so much design history locked into one environmentally controlled room, it’s hard to know where to start. Taking advantage of the one-to-one interaction with the person who, arguably, is the most in–the-know when it comes to the history of design, I decide to launch into the interview by asking a few questions that would bring me up to speed on 19th century design and the Arts & Crafts movement that influenced a change of direction in interior design. And to not get lost in the library, I decided to focus on one influential character in the evolution of this movement, William Morris.

Since you’re here, why not check out the latest Morris & Co. collection inspired by the decorative interiors of Emery Walker’s House

Image credit: Morris & Co

Hamish Kilburn: Catherine, what is the Arts & Crafts movement and how did it start?

Catherine Sidwell: The late nineteenth century Arts & Crafts movement was focused on honesty in craftsmanship, truth to materials, simplicity in design, and an emphasis on the beauty of natural colours and materials, such as wood. This movement began in England and those involved with its development placed great value on the hand crafts and sought to elevate the status of decorative arts at that time to be equal to the fine arts and architecture. Late nineteenth century publications which illustrated the work of Arts and Crafts designers influenced the development of the Arts and Crafts movement in Europe, North America and beyond.

HK: Who was behind this movement and what were they reacting to?

CS: Those behind the movement were a young and influential and affluent group of architects, craftspeople, and designers that took inspiration largely from nature and who had a deep appreciation for the medieval arts and crafts from Britain, northern Europe, and the Middle East.

During a period when mostly fine art and sculpture was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London, a group of men who were to become prominent figures of the Arts and Crafts movement founded the Art Workers Guild in London in 1884, William Morris (1834-1896) was elected as Master of the Guild in 1892. The group met to discuss their ideas and techniques with a goal of elevating the profile of what had been regarded as the ‘lesser arts.’ The term Arts & Crafts was coined after the formation of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1887, which displayed their work to the buying public. The result of such a movement raised the social and intellectual status of all crafts, including textiles, ceramics, metalwork, and furniture.

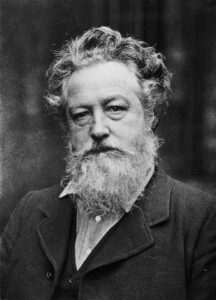

Image caption: Black & White archival William Morris (image 1887). | Image credit: Sanderson Design Group

HK: How prominent was William Morris in this movement and what motivated him?

CS: William Morris is widely recognised as a leading figure in the Arts & Crafts movement and his bust is a centrepiece at the Art Worker’s Guild building in London today. He started by creating simple, beautiful furnishings for the home for himself, friends, and acquaintances, often in collaboration, due to a frustration at not being able to find the designs he wanted for his own home. He established Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co in 1861, with his friends, later the firm became Morris & Co.

The fashion for wealthy, middle-class homeowners in Britain at this time was to furnish their homes with a mixture of heavy, dark, and overly ornate machine-produced furniture, with dense layers of different fabrics. Designs for wallpapers and textiles were often very naturalistic in their representations of nature and a three-dimensional effect was often achieved giving the impression of depth with the use of shading to represent shadows.

Morris had a deep dislike for mass produced furniture for the home preferring hand produced historical craft pieces inspired by nature and natural materials. His childhood experience of wandering through Epping Forest, northeast of London; viewing medieval tapestries in an Elizabethan hunting lodge; and reading romantic literature and poetry had a deep and lasting impact. Morris went on to champion the revival of the hand crafts and inspired others to follow. By creating designs for wallpapers, textiles, furniture, stained glass, and tiles, and making them available to the late 19th century market for interior decoration he changed the fashion in which homes were furnished. In 1883 Morris also devoted his time to the Social Democratic Federation advocating for restrictions on worker’s hours and better housing and became a known socialist.

“We know William Morris today as the creator of beautiful patterns for wallpapers and textiles, however, there was much more to him.” Catherine Sidwell, Senior Archivist, Sanderson Design Group

There is so much more to William Morris than being the creator of beautiful designs for wallpapers and textiles. While studying Classics at Oxford, Morris made lasting friendships with John Ruskin, Edward Burne-Jones, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the Pre-Raphaelite painters. With initial intentions to join the church, Morris became so inspired by his contemporaries that he tried his hand at being an artist and poet and trained for nine months as an architect in the office of George Edmund Street in Oxford. In 1877, Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in response to the conservation problems of the 19th century. This Society continues to be influential today.

Through his lifetime, Morris studied a variety of crafts and became skilled at drawing, oil painting, mural decoration, stained glass, embroidery, tapestry weaving, dyeing, calligraphy, illuminations, typography, and bookmaking. In the late 1860s and early 1870s he also translated Icelandic sagas and medieval French tales.

HK: What techniques and materials did Morris apply to his work?

CS: Morris worked hard to create honest, two-dimensional, or ‘flat’ representations of natural forms, as opposed to the fashionable and expensive highly naturalistic botanical representations of flowers and plants. He used bold primary motifs with often a secondary smaller, simpler background for many of his designs. His preference was not to copy nature in its entirety but to represent nature, without creating three-dimensional depth.

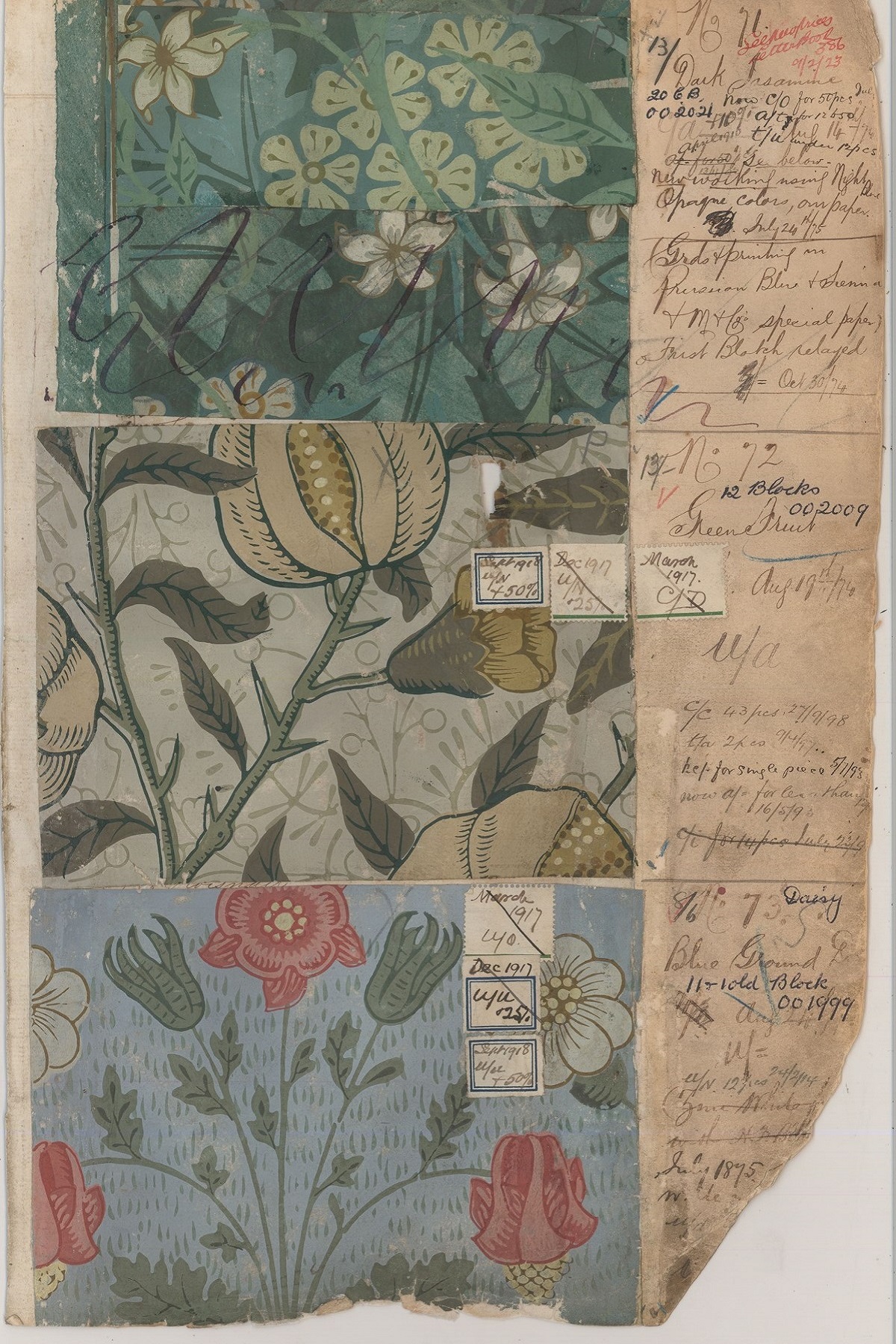

Morris created designs for a wide range of textiles, including embroideries, printed cottons for furnishings and woven wool fabrics that were used as curtains, decorative tapestries, and carpets. Morris moved his business to Merton Abbey, near Wimbledon in South London, in 188. There he leased a textile printing workshop complete with a water wheel and land on both sides of the river Wandle. His iconic textiles were made within weatherboarded buildings using dye vats, printing tables, looms for carpets and tapestries and a stained-glass workshop. He employed skilled weavers and local apprentices who learned the hand crafts. John Henry Dearle (1859-1932) was a young apprentice and soon became an expert pattern designer when he took over the creative direction of Morris and Co. after William Morris’ death in 1896.

Image credit: Morris & Co

HK: Please describe some of Morris’ earlier well-known interior designs?

CS: Morris travelled throughout northern Europe and was inspired by French medieval art, architecture, and interiors. These extensive travels influenced the creation of the Red House in Kent, designed by his close friend and architect Phillip Webb. The house was decorated with a painted ceiling in the hall, wall paintings, embroideries, wall paintings, and stained glass.

Later Morris and his wife Jane had homes close to the river Thames. Their country house Kelmscott Manor, a limestone manor house in the village of Kelmscott, West Oxfordshire, was built in 1570 with a late 17th century wing. Morris’s book News from the Nowhere, published in 1890, includes descriptions of his impressions of the house and its surroundings. He described the village as ‘heaven on earth’ and unspoilt and unpretentious. The couple’s other house, a Georgian brick building dates from 1785 and this was William and Jane’s town house on the river front at Hammersmith. The interiors of both homes were decorated with wallpapers and textiles designed by William and produced by Morris & Co.

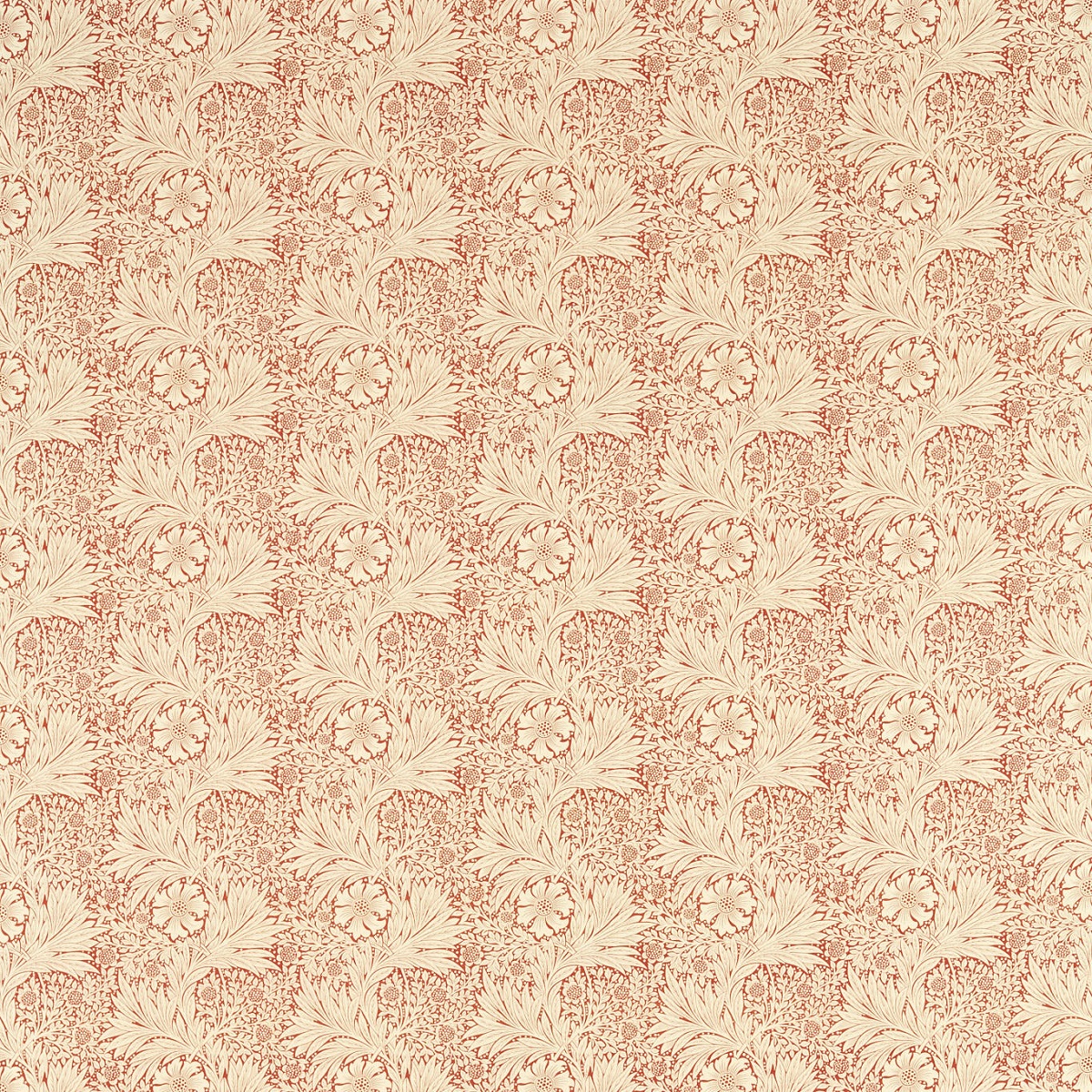

Morris’ experience of nature in the countryside inspired many of his designs representing flora and fauna that we can identify as native to the British countryside, such as the Acanthas and Marigold designs. Originally imagined as a furnishing fabric, Marigold is an 1875 William Morris design filled with charm and energy with swirling movement.

Image credit: Sim Canetty-Clarke / The Fife Arms

HK: Where have Morris’ archive prints been used in a commercial setting today?

CS: There have been many in recent years but one that stands out is The Fife Arms, a historical building that has been at the heart of Braemar, the town famous for the annual Highland Games that draws visitors from around the world. Reopening at the end of 2018, this Victorian coaching inn has been rewoven for the 21st century by its new owners, Iwan and Manuela Wirth, Co-Presidents of the international gallery Hauser & Wirth, under the banner of their hospitality company, Artfarm, which also includes The Audley Public House and Mount St. Restaurant in London’s Mayfair.

The interiors by Russell Sage feature a thoughtful collection of historic objects, whimsical curios, artwork, and artefacts, as well as newly commissioned contemporary works. A strong Scottish narrative, often local to Braemar itself, runs throughout the entire hotel making it a repository of stories and anecdotes. The Fife Arms offers accommodation across 46 sumptuous bedrooms, each with unique furnishings and decorations.

Image credit: Sanderson Design Group

HK: Where can we find archived Morris & Co. prints in a new collection?

CS: The 2023 Morris & Co. collection Outdoor-Performance is a versatile range that has returned historic fabric designs, such as Acanthas and Marigold, to the place that originally inspired them – nature and the outdoors. This new collection has united the two great threads in 19th-century designer William Morris’s creative life – beauty and utility – with twenty-five enduring fabrics perfect for busy homes, gardens, patios, and poolside. A dedicated team of makers at Sanderson Design Group’s Standfast Factory, Lancaster, have incorporated innovative materials and techniques to ensure durability for both indoor and outdoor use. Including UV and water resistance, wipeable finishes, anti-microbial and colourfast properties, these treatments have prepared these fabrics for the hustle and bustle of daily life for any commercial property.

Sanderson Design Group is one of our Recommended Suppliers and regularly features in our Supplier News section of the website. If you are interested in becoming one of our Recommended Suppliers, please email Katy Phillips.